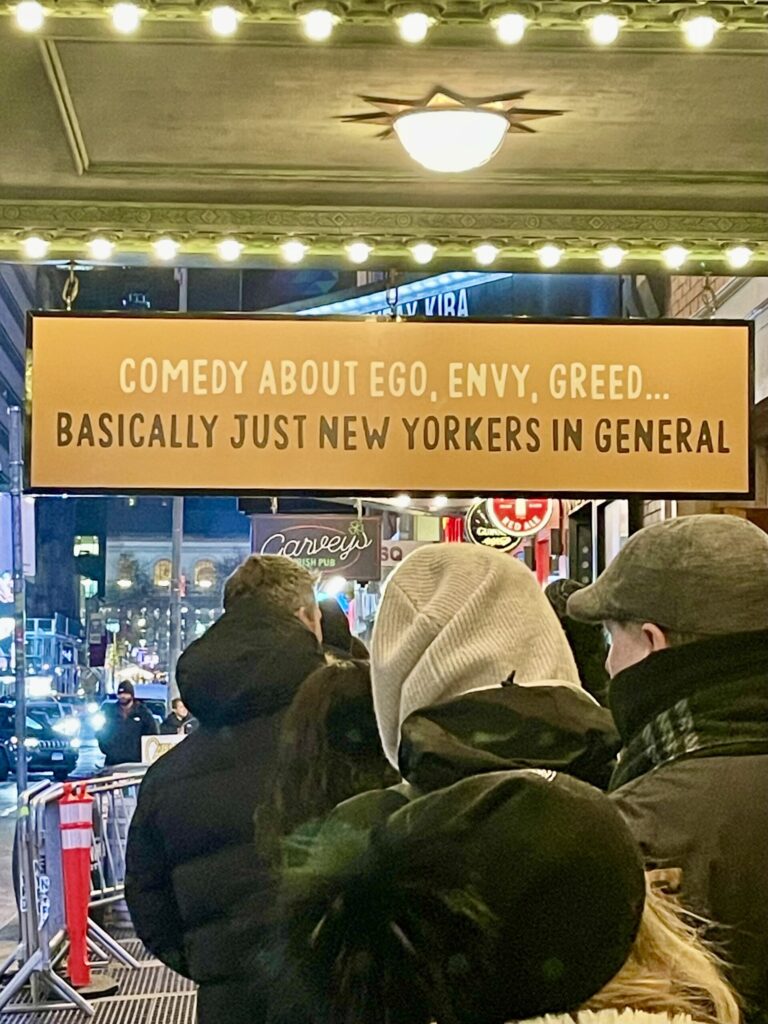

All Out: Comedy About Ambition on Broadway is one of those nights at the theater that feels less like a traditional show and more like a cultural sampler platter. It’s ambitious, messy, occasionally brilliant, and undeniably New York. It stars Jim Gaffigan, Wayne Brady, Cecily Strong, and Ben Schwartz, with music performed live by the band Lawrence, the brother-sister group led by Gracie Lawrence and Clyde Lawrence. The connective tissue holding it all together is the writing of Simon Rich, whose sketch comedy and short stories provide the narrative backbone.

Let’s start with the clearest win of the evening: the music. Lawrence is superb. Their sound is energetic, original, and joyfully skilled but unpolished (as rock and roll should be) in a way that feels rare on Broadway, where music is often sanded down until it gleams. This band thrives on groove, momentum, and ensemble precision. Every member onstage radiates musicianship, and the arrangements feel alive rather than locked into a rigid theatrical mold. At many moments, All Out briefly transforms into a concert you didn’t realize you were craving, the kind that reminds you how thrilling it is to watch musicians who genuinely enjoy playing together.

The challenge is that the show isn’t really about Lawrence, at least not fully. Instead, the music shares space with a series of narrated and performed quirky but ambitions stories by Simon Rich, each tailored to a specific actor. Rich’s writing is quirky, clever, and conceptually playful, often hinging on an absurd premise that refracts something quietly human. These stories are well suited to the performers, but they also reveal the show’s central tension: while the ideas are inventive, they don’t always have the substance or comedic firepower to stand entirely on their own.

Ben Schwartz plays a key role in the lineup, offering an elegant cadence to his reading and a performance rich with emotively engaging facial expressions. He fully delivers on the storytelling, first embodying an overly entitled, privileged fox and then an emperor with no clothes, clinging desperately to illusion. Schwartz balances manic energy with precise control, allowing the emperor’s unraveling to feel both comic and relatable. When a child finally refuses to play along with the lie, the emperor is forced into a reckoning, coming to terms with his own shortcomings not just as a ruler, but as a person. The result is a performance that channels Schwartz’s self-aware humor into something sharper, more reflective, and quietly affecting.

Jim Gaffigan’s segment centers on Clobbo, a beastly, destructive man with massive hands and buckets on his feet, who earns a promotion to management as a reward for violently dispatching invading alien bugs that threatened the human race. It’s a darkly funny corporate satire, complete with an insubordinate underling played by Gracie Lawrence, skewering the strange ways organizations reward achievement only to undermine careers by slowly but intentionally boxing them out of important meetings and conversations. Gaffigan’s deadpan delivery does much of the heavy lifting, grounding the absurdity in his familiar, understated rhythm. The idea is sharp; the execution is solid, and the part where Clobbo tries to sit like a normal human being on a company couch is hilarious.

Wayne Brady, meanwhile, plays Oatsy, the long-suffering horse of Paul Revere, grappling with the indignity of historical invisibility despite his crucial role in American lore. Brady brings musicality, vulnerability, and quiet frustration to the role, turning a novelty premise into something surprisingly reflective about credit, legacy, and erasure. Watching Oatsy navigate the stages of depression and his deteriorating marriage was oddly poignant, especially as Paul Revere replaces Oatsy with a new, more attractive horse that suits Revere’s rocketing fame. When Oatsy’s chance at redemption finally arrives, we all learn a lesson about human selfishness and how history is rarely ever completely truthful.

Cecily Strong delivers one of the evening’s most resonant pieces, a first-person narrative told from the point of view of New York City itself. The city speaks with a weary affection, describing its love-hate relationship with the young dreamers who arrive full of ambition and leave either transformed or defeated, driving their belongings home on empty roads the city cleared for escape. But, she admits, some do stay, become full-fledged adults in NYC, and in turn help those arriving younger versions of themselves. Strong’s performance balances warmth, sarcasm, and melancholy, capturing the emotional whiplash of a place that promises everything and guarantees nothing. For anyone who has lived here long enough (especially in Hell’s Kitchen, where my wife and I live) the piece lands with particular force. At some point, we all need health insurance.

And yet, despite these individual pleasures, All Out feels fractured. The components never quite coalesce into a unified whole. Lawrence’s music could carry an entire evening on its own. Simon Rich’s stories are clever but often feel more like polished literary magazine fiction pieces than theatrical centerpieces. Pairing them together seems like a strategic attempt to create a collective force of talent that justifies Broadway-level ticket prices. Judging by the online reviews on Reddit and social media, the jury of public opinion appears unconvinced.

For my wife and me, the value equation worked. She scored discount tickets, and at that price point the night felt absolutely worth it. There’s something to be said for a show that swings big, even if it doesn’t always connect. Broadway doesn’t need more safe bets; it needs more experiments, even flawed ones.

There was also a light personal layer to the evening that no critic’s review can account for. If you live in New York City long enough, you cross paths with people in the entertainment world in ways that feel surreal and oddly natural. Seeing Jim Gaffigan onstage reminded me that I once sat beside him at a Story Collider event where his wife, Jeannie, shared her harrowing story of surviving a brain tumor the size of a pear. That show, improbably, was the last event my wife and I attended before COVID shut the world down hours later.

During the pandemic, we became regulars at Linda Loves Bingo, where Cecily Strong often appeared, an experience she later referenced in her memoir This Will All Be Over Soon. None of this makes All Out a better or worse show. But it does underscore why nights like this feel uniquely New York: the city collapses distances, blurs lines between audience and artist, and turns coincidence into connection.

All Out may not fully work as a cohesive Broadway event. But many parts of it shine brightly, especially the music. And sometimes, in this city that destroys so many dreamers, that’s enough of a win for creative souls who never gave up on creating their art.

See you under the marquee. – Jim Thompson