Chess explores complex human dramas such as high-stakes geopolitics, the enduring power of family, and the smartest love triangle in Broadway history. But it’s also about something far more subtle, sinister, and powerful: mental illness.

On the surface, the story in Chess is driven by clandestine government agencies navigating international power plays, the personal ambition of two complicated geniuses, and the human need for long-term companionship—but all of those key forces are shaped by mental illness. In particular, the mental illness of the American chess prodigy and revered champion, Freddi Trumper (Aaron Tveit), whose brain chemistry renders him a celebrated master of his craft in public, but also a helpless puddle on negative thoughts and destructive emotions in private, especially when he is off of his medication.

If you think the world feels precarious now, in Chess, the entire fate of the human race is contingent on how well Freddi Trumper can control his bipolar disorder (he suffers from paranoid schizophrenia in earlier versions of the show). Mental illness, as we know, impacts not just the individual, but everyone in their family and sphere of influence. For Freddi Trumper, that sphere is centered around Florence Vassy (Lea Michele), his onsite assistant and coach, but also his lover, whose devotion to Freddi is deep and heartfelt but also limited by the preservation of her own sanity and survival.

Enter Anatoly Sergievsky (Nicholas Christopher), Freddie’s heralded chess rival and Russian nemesis, who falls in love with Florence, whose allegiance to Freddi wanes as the constant drudgery of having to navigate his scary outbursts and mental illness drains her own life force. In storytelling, love triangles can feel contrived, but it’s logical that Florence would be driven to an exceptionally talented chess genius who offers an unique understanding of her increasingly desperate situation and human needs. Anatoly, whose personal life was meticulously orchestrated by the KGB, struggles between choosing a fulfilling life with the Hungarian-born Florence in England and his wife and children in Russia, whom he feels a deep obligation to as a husband and father.

The intrigue escalates when we learn the Russians may or may not have Florence’s aging father, Gregor, who disappeared during the Hungarian revolution in 1956, imprisoned in a remote work camp. The Russians leverage the prospect of reuniting the father and daughter as powerful bargaining point to sway Florence’s ultimate fateful decisions regarding her future and the future of the men in her life.

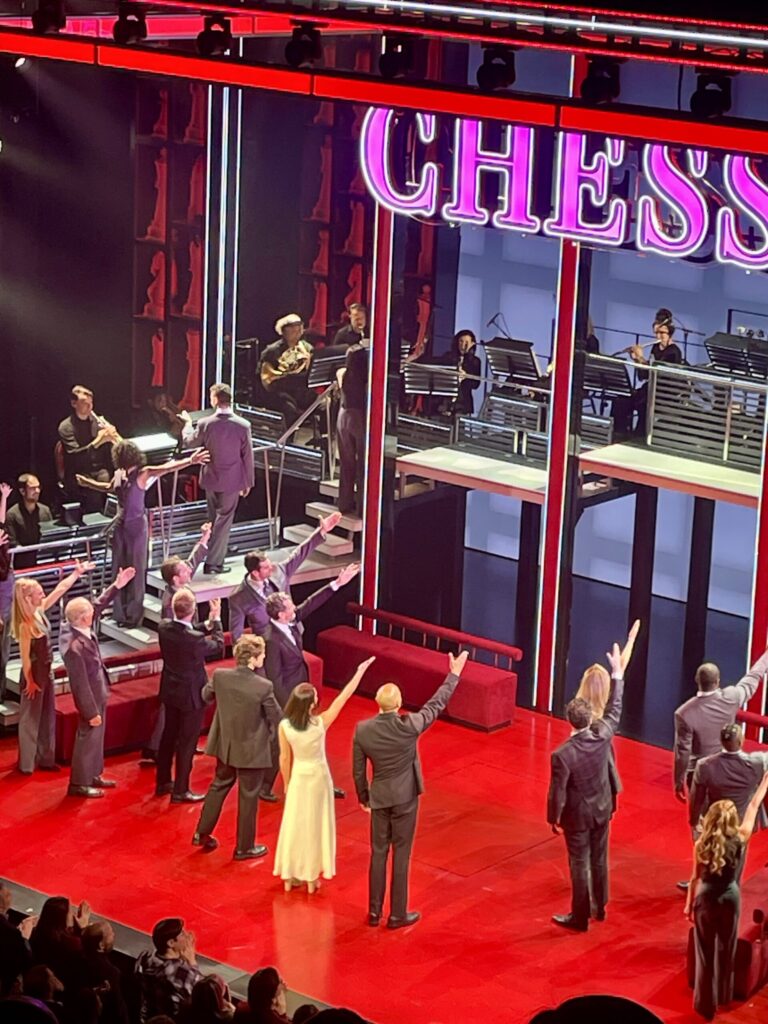

I’m not providing any spoilers other than these dramatic and compelling dynamics make for stirring songs performed by some of the most talented actors on Broadway, engaging characters that are accessible despite their wizard-like intelligence and demons, and well-timed zingers that highlight the absurdity of it all, most notably the rivalry between Russia and a United States that “hates chess.”

Shout out to director Michael Mayer for folding in unavoidable modern-day political and cultural references to a show imbued with the crazy and tragic genetics of the 1980s—which were plagued not only by the threat of nuclear war, but the social upheaval driven by skyrocketing wealth of America’s elite and the behind-the-scenes rise of AIDs, cocaine addiction, and a darkening horizon over a Broadway show that seemed as cursed as its characters.

For more eye-opening details regarding the story behind the creation of Chess, I strongly suggest you read Chapter Twenty-Three, “End of the Line,” of Razzle Dazzle by Michael Riedel. Here is an excerpt detailing the struggles of Michael Bennett (April 1943 – July 1987):

So, here we are in 2025, attending a show that originally debuted at Broadway’s Imperial Theatre on April 28, 1988, featuring songs crafted by ABBA, narratives shaped by U.S.-Russian diplomacy, and a love story about immigrants trying to resolve where they are with where they came from. Some things never change. Including the timeless ubiquity of ABBA.

For Cold War kids like me who grew up under the constant threat to total annihilation, Chess transports us back to a time that feels both familiar and unsettlingly quaint. The world back then was equally dangerous but much simpler, where death and destruction would arrive fast but uncomplicated by toxic social media, predatory algorithms, and a U.S. government that was not overthrown by the Cubans in Red Dawn but by bigoted Fox News-watching Americans who voted for authoritarianism.

Where’s that 1980s cocaine escapism when you need it?

Finally, you’ll notice that my reviews on Broadway for Bros focus more on the creative impact and cultural relevance of Broadway shows. This is my way of celebrating the art and industry while also avoiding my ignorance of the more technical and critique-driven observations that I—as a Broadway newbie—cannot provide. I simply do not have the experience or credentials.

That said, it is worth noting that both my wife and I strained to understand some of the lyrics, which are critical to the storytelling, in many of the songs because they were overpowered by the on-stage orchestra. This may have been due to the “partially obstructed” seats that my wife and I had because we’re not wealthy finance folks but still love live Broadway and a good cheap-seat deal. Though “partially obstructed” seats are hit or miss, our experiences lean strongly and favorably in the “hey these seats are pretty great” direction. I also feel an unspoken camaraderie amongst those of us who sit together in the working class sections of Broadway theaters. Anyway, let me know if you saw Chess and had a similar experience.

See you under the marquee. — Jim Thompson