This Broadway for Bros review of Kyoto is biased, subjective, and yes, I think I deserve a Tony nomination.

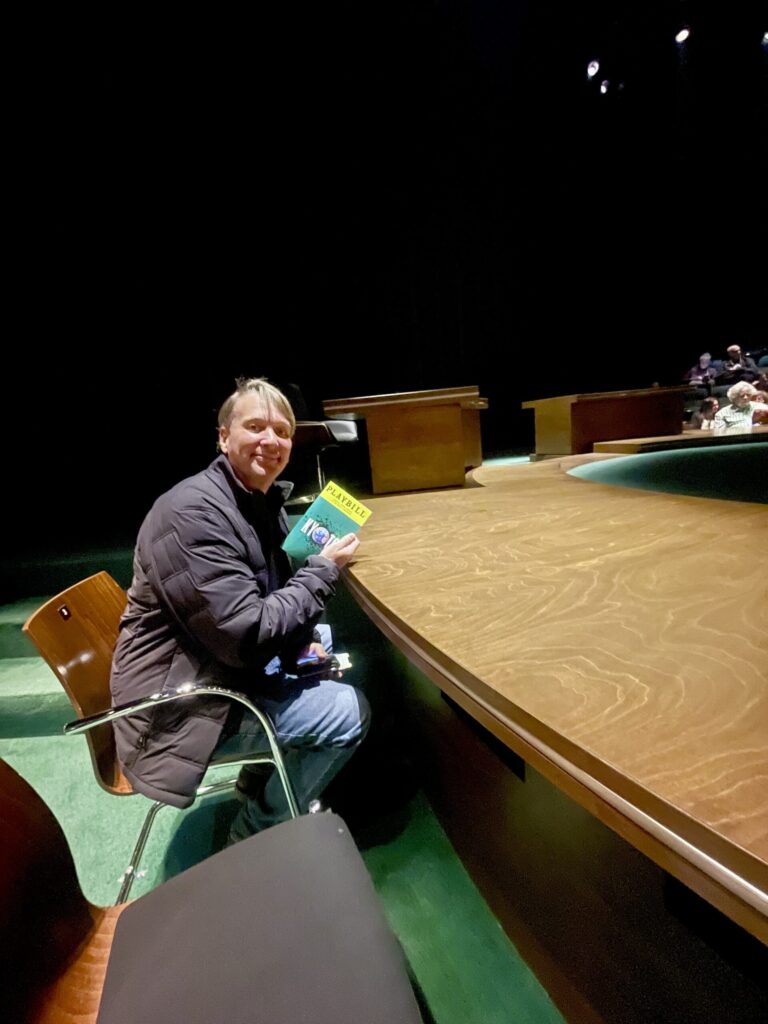

That’s because my wife—who is both a seasoned expert at winning discounted Broadway tickets and, apparently, fate’s chosen climate negotiator—somehow secured us seats at the conference table itself, the very table around which much of Kyoto unfolds. Not near it. Not adjacent to it. At it. We were delegates. We were props. We were silent witnesses and occasionally complicit nodders in one of the most morally complex stories Broadway has put onstage in years.

Actors made eye contact with us and gestured at us as they passionately debated the world’s most existential threat, climate change, while defending the interest of their global constituents. We nodded on cue as they guffawed, grimaced, and shuffled papers that held the consequential complexities of policy implications. I am convinced the show ran especially smoothly that night because of our subtle but vital support. It was surreal, exhilarating, and—for this introvert—mildly panic-inducing in the best possible way. After I sat down I looked up at hundreds of people looking down at me. I’m not used to that. But I digress.

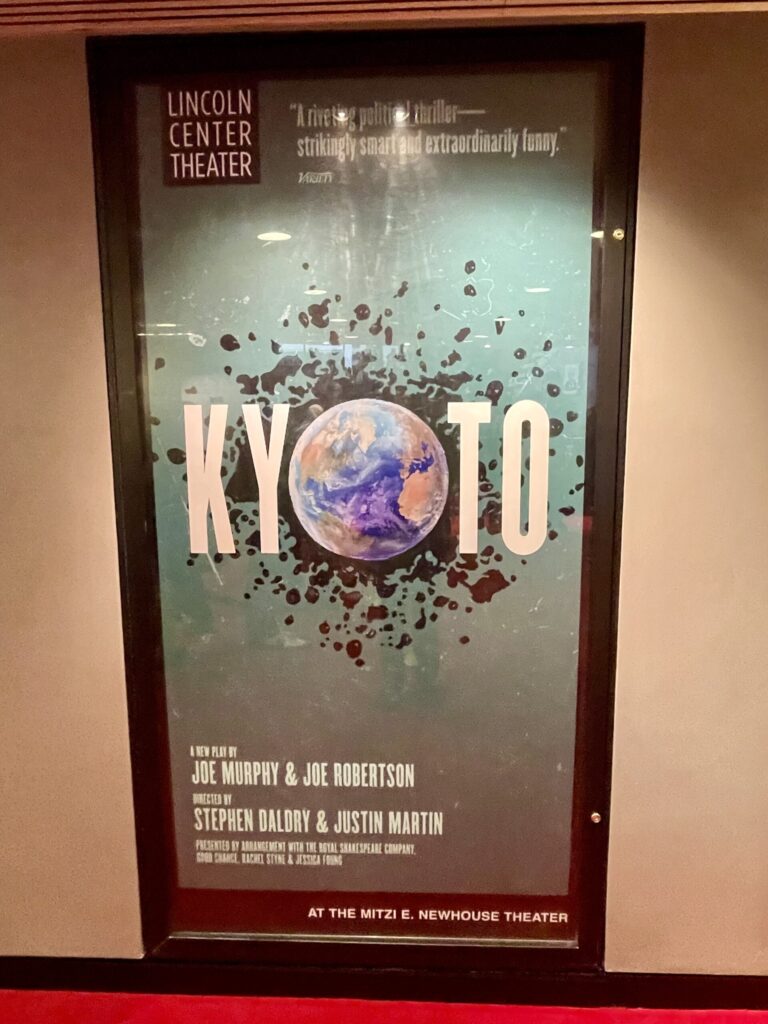

Kyoto dramatizes the high-stakes negotiations leading up to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the landmark international agreement aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Set largely inside the Kyoto International Conference Center in December 1997, the play captures the collision of national interests, economic power, scientific urgency, and raw human ego as representatives from around the world confront a climate crisis that threatens everyone, even as they fiercely defend their own interests.

Island nations face literal annihilation as rising sea levels threaten their existence. Developing countries argue—reasonably—that they should not be held to the same environmental standards as nations that already built their wealth by burning fossil fuels. Meanwhile, the United States arrives armed with lawyers, lobbyists, and the quiet confidence of a global superpower accustomed to bending the rules when the rules become inconvenient.

At the center of the American strategy is Don Pearlman, an oil industry lobbyist and political tactician brought chillingly to life by Stephen Kunken. Kunken delivers one of those performances that makes you admire the craft while deeply resenting the character. Pearlman is sharp, relentless, and frighteningly persuasive. He does not see himself as a villain. He truly believes that he is defending capitalism, American prosperity, and geopolitical balance against what he views as opportunistic maneuvering by China and economically disadvantaged nations seeking to constrain the U.S. while exempting themselves.

That moral framing is what makes Kyoto so unsettling. The play refuses to offer easy heroes or cartoon villains. Instead, it exposes how intelligent, articulate people can rationalize decisions that collectively steer us toward catastrophe. Pearlman’s arguments are coherent. His logic is relentlessly consistent with his worldview. And that’s the problem.

Standing in quiet but resolute contrast is Argentina’s delegate Raúl, portrayed with understated conviction by Jorge Bosch, whose performance radiates a stubborn optimism and an unshakable belief that doing the right thing—for the planet and for the people who depend on it—is still possible. His determination feels almost radical in a room defined by compromise and calculation, a reminder of what moral clarity looks like when it refuses to bend. Seen on the stage of Lincoln Center Theater, that contrast lands with particular force, underscoring the stakes of every argument played out before us.

The Kyoto Conference itself was the culmination of decades of negotiation following growing scientific consensus about climate change. The protocol that emerged required industrialized nations to reduce emissions, while granting developing countries more flexibility—a compromise that infuriated many U.S. lawmakers and ultimately led the United States to sign but never ratify the agreement. That historical reality hangs over the play like a storm cloud. As an audience member, you know how this ends. And yet watching it unfold in real time—sitting at the conference table, no less—makes the failure feel newly personal.

What Kyoto does exceptionally well is dramatize process. This is not a show about protests in the streets or apocalyptic futures. It’s about wording. Commas. Side meetings. Strategic delays. Who controls the narrative and who controls the clock. It understands that history is often shaped not by speeches, but by procedural maneuvering and exhausted negotiators making compromises at 3 a.m.

Could the show have been as captivating, provocative, and poignant without my involvement? Probably. Hah. The real takeaway from my experience with Kyoto is that human beings are, as a species, greedy, short-sighted, and predatory—and also capable of reflection, cooperation, and moments of genuine moral reckoning. The future of our species, like our planet’s environment, thrives or collapses based on whether people are willing to act beyond narrow self-interest.

For me, Kyoto became a deeply complicated meditation on what it means to be American. What it means to be born into a wealthy country that has provided extraordinary advantages—and what it means when that same country uses its power to bully, stall, and sabotage collective efforts to address an existential threat, all to keep money flowing into already full pockets.

This is Broadway operating at its highest level: telling stories that are important, difficult, and uncomfortable. Stories that force self-awareness not just on individuals, but on nations and alliances built on shared greed and mutual denial. Kyoto doesn’t let you leave feeling virtuous. It leaves you implicated.

And if Broadway for Bros has a mission, it’s this: shows don’t have to be musicals, or uplifting, or escapist to be worth your time. Sometimes the best night at the theater is the one where you walk out unsettled, arguing, and quietly wondering how many disasters in history were decided around tables just like the one you were lucky—or unlucky—enough to sit at.